- Home

- Sarah Weinman

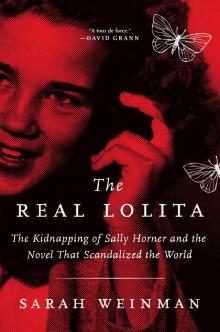

The Real Lolita

The Real Lolita Read online

Dedication

For my mother

Epigraphs

You have to be an artist and a madman, a creature of infinite melancholy, with a bubble of hot poison in your loins and a super-voluptuous flame permanently aglow in your subtle spine (oh, how you have to cringe and hide!), in order to discern at once, by ineffable signs—the slightly feline outline of a cheekbone, the slenderness of a downy limb, and other indices which despair and shame and tears of tenderness forbid me to tabulate—the little deadly demon among the wholesome children; she stands unrecognized by them and unconscious herself of her fantastic power.

—Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

I want to go home as soon as I can.

—Sally Horner, March 21, 1950

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraphs

Introduction: “Had I Done to Her . . . ?”

One: The Five-and-Dime

Two: A Trip to the Beach

Three: From Wellesley to Cornell

Four: Sally, at First

Five: The Search for Sally

Six: Seeds of Compulsion

Seven: Frank, in Shadow

Eight: “A Lonely Mother Waits”

Nine: The Prosecutor

Ten: Baltimore

Eleven: Walks of Death

Twelve: Across America by Oldsmobile

Thirteen: Dallas

Fourteen: The Neighbor

Fifteen: San Jose

Sixteen: After the Rescue

Seventeen: A Guilty Plea

Eighteen: When Nabokov (Really) Learned About Sally

Nineteen: Rebuilding a Life

Twenty: Lolita Progresses

Twenty-One: Weekend in Wildwood

Twenty-Two: The Note Card

Twenty-Three: “A Darn Nice Girl”

Twenty-Four: La Salle in Prison

Twenty-Five: “Gee, Ed, That Was Bad Luck”

Twenty-Six: Writing and Publishing Lolita

Twenty-Seven: Connecting Sally Horner to Lolita

Twenty-Eight: “He Told Me Not to Tell”

Twenty-Nine: Aftermaths

Epilogue: On Two Girls Named Lolita and Sally

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Notes

Index

About the Author

Also by Sarah Weinman

Copyright

Permissions

About the Publisher

Introduction

“Had I Done to Her . . . ?”

“Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?”

—Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

A couple of years before her life changed course forever, Sally Horner posed for a photograph. Nine years old at the time, she stands in front of the back fence of her house, a thin, leafless tree disappearing into the top right-hand corner of the frame. Tendrils of Sally’s hair brush her face and the top shoulder of her coat. She looks straight ahead at the photographer, her sister’s husband, trust and love for him evident in her expression. The photo has a ghostly quality, enhanced by the sepia color and the blurred focus.

This wasn’t the first photograph of Sally Horner that I saw, and I’ve seen a great many more since. But this is the one I think of the most. Because it’s the only photo where Sally has a child’s utter lack of guile, without any idea of what horrors lie ahead. Here was evidence of one future she might have had. Sally didn’t have a chance to live that one out.

Florence “Sally” Horner, age nine.

FLORENCE “SALLY” HORNER disappeared from Camden, New Jersey, in mid-June 1948, in the company of a man calling himself Frank La Salle. Twenty-one months later, in March 1950, with the help of a concerned neighbor, Sally telephoned her family from San Jose, California, begging for someone to send the FBI to rescue her. Sensational coverage and La Salle’s hasty guilty plea ensued, and the man spent the remainder of his life in prison.

Sally Horner, however, had only two more years to live. And when she died, in mid-August 1952, news of her death reached Vladimir Nabokov at a critical time in the creation of his novel-in-progress—a book he had struggled with, in various forms, for more than a decade, and one that would transform his personal and professional life far beyond his imaginings.

Sally Horner’s story buttressed the second half of Lolita. Instead of pitching the manuscript into the fire—Nabokov had come close twice, prevented only by the quick actions of his wife, Véra—he set to finish it, borrowing details from the real-life case as needed. Both Sally Horner and Nabokov’s fictional creation Dolores Haze were brunette daughters of widowed mothers, fated to be captives of much older predators for nearly two years.

Lolita, when published, was infamous, then famous, always controversial, always a topic of discussion. It has sold more than sixty million copies worldwide in its sixty-plus years of life. Sally Horner, however, was largely forgotten, except by her immediate family members and close friends. They would not even learn of the connection to Lolita until just a few years ago. A curious reporter had drawn a line between the real girl and the fictional character in the early 1960s, only to be scoffed at by the Nabokovs. Then, around the novel’s fiftieth anniversary, a well-versed Nabokov scholar explored the link between Lolita and Sally, showing just how deeply Nabokov embedded the true story into his fiction.

But neither of those men—the journalist or the academic— thought to look more closely at the brief life of Sally Horner. A life that at first resembled a hardscrabble American childhood, then became something extraordinary, then uplifting, and, last of all, tragic. A life that reverberated through the culture, and irrevocably changed the course of twentieth-century literature.

I TELL CRIME STORIES for a living. That means I read a great deal about, and immerse myself in, bad things happening to people, good or otherwise. Crime stories grapple with what causes people to topple over from sanity to madness, from decency to psychopathy, from love to rage. They ignite within me the twinned sense of obsession and compulsion. If these feelings persist, I know the story is mine to tell.

Some stories, I’ve learned over time, work best in short form. Others break loose from the artificial constraints of a magazine article. Without structure I cannot tell the story, but without a sense of emotional investment and mission, I cannot do justice to the people whose lives I attempt to re-create for readers.

Several years ago I stumbled upon what happened to Sally Horner while looking for a new story to tell. It was my habit then, and remains so now, to plumb obscure corners of the Internet for ideas. I gravitate toward the mid-twentieth century because that period is well documented by newspapers, radio, even early television, yet just outside the bounds of memory. Court records still exist, but require extra rounds of effort to uncover. There are people still alive who remember what happened, but few enough that their recollections are on the cusp of vanishing. Here, in that liminal space where the contemporary meets the past, are stories crying out for greater context and understanding.

Sally Horner caught my attention with particular urgency. Here was a young girl, victimized over a twenty-one-month odyssey from New Jersey to California, by an opportunistic child molester. Here was a girl who figured out a way to survive away from home against her will, who acted in ways that baffled her friends and relatives at the time. We better comprehend those means of survival now because of more recent accounts of girls and women in captivity. Here was a girl who survived her ordeal when so many others, snatched away from their lives, do not. Then for her to die so soon after her rescue, her story subsumed by a novel, one of the most iconic, important works of the twent

ieth century? Sally Horner got under my skin in a way that few stories ever have.

I dug for the details of Sally’s life and its connections to Lolita throughout 2014 for a feature published that fall by the Canadian online magazine Hazlitt. Even after chasing down court documents, talking to family members, visiting some of the places she had lived—and some of the places where La Salle took her—and writing the piece, I knew I wasn’t finished with Sally Horner. Or, more accurately, she was not finished with me.

What drove me then and galls me now is that Sally’s abduction defined her entire short life. She never had a chance to grow up, pursue a career, marry, have children, grow old, be happy. She never got to build on the fierce intelligence so evident to her best friend that, nearly seven decades later, she spoke to me of Sally not as a peer, but as a mentor. After Sally died, her family rarely mentioned her or what had happened. They didn’t speak of her with awe, or pity, or scorn. She was only an absence.

For decades Sally’s claim to immortality was as an incidental reference in Lolita, one of the many utterances by the predatory narrator, Humbert Humbert, that allows him to control the narrative and, of course, to control Dolores Haze. Like Lolita, Sally Horner was no “little deadly demon among the wholesome children.” Both girls, fictional and real, were wholesome children. Contrary to Humbert Humbert’s assertions, Sally, like Lolita, was no seductress, “unconscious herself of her fantastic power.”

The fantastic power both girls possessed was the capacity to haunt.

I FIRST READ LOLITA at sixteen, as a high school junior whose intellectual curiosity far exceeded her emotional maturity. It was something of a self-imposed dare. Only a few months earlier I’d breezed through One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Some months later I’d reckon with Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth. I thought I could handle what transpired between Dolores Haze and Humbert Humbert. I thought I could appreciate the language and not be affected by the story. I pretended I was ready for Lolita, but I was nowhere close.

Those iconic opening lines, “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta,” sent a frisson down my adolescent spine. I didn’t like that feeling, but I wasn’t supposed to. I was soon in thrall to Humbert Humbert’s voice, the silken veneer barely concealing a loathsome predilection.

I kept reading, hoping there might be some salvation for Dolores, even though I should have known from the foreword, supplied by the fictional narrator John Ray, Jr., PhD, that it does not arrive for a long time. And when she finally escapes from Humbert’s clutches to embrace her own life, her freedom is short-lived.

I realized, though I could not properly articulate it, that Vladimir Nabokov had pulled off something remarkable. Lolita was my first encounter with an unreliable narrator, one who must be regarded with suspicion. The whole book relies upon the mounting tension between what Humbert Humbert wants the reader to know and what the reader can discern. It is all too easy to be seduced by his sophisticated narration, his panoramic descriptions of America, circa 1947, and his observations of the girl he nicknames Lolita. Those who love language and literature are rewarded richly, but also duped. If you’re not being careful, you lose sight of the fact that Humbert raped a twelve-year-old child repeatedly over the course of nearly two years, and got away with it.

It happened to the writer Mikita Brottman, who in The Maximum Security Book Club described her own cognitive dissonance discussing Lolita with the discussion group she led at a Maryland maximum-security prison. Brottman, reading the novel in advance, had “immediately fallen in love with the narrator,” so much so that Humbert Humbert’s “style, humor, and sophistication blind[ed] me to his faults.” Brottman knew she shouldn’t sympathize with a pedophile, but she couldn’t help being mesmerized.

The prisoners in her book club were nowhere near so enchanted. An hour into the discussion, one of them looked up at Brottman and cried, “He’s just an old pedo!” A second prisoner added: “It’s all bullshit, all his long, fancy words. I can see through it. It’s all a cover-up. I know what he wants to do with her.” A third prisoner drove home the point that Lolita “isn’t a love story. Get rid of all the fancy language, bring it down to the lower [sic] common denominator, and it’s a grown man molesting a little girl.”

Brottman, grappling with the prisoners’ blunt responses, realized her foolishness. She wasn’t the first, nor the last, to be seduced by style or manipulated by language. Millions of readers missed how Lolita folded in the story of a girl who experienced in real life what Dolores Haze suffered on the page. The appreciation of art can make a sucker out of those who forget the darkness of real life.

Knowing about Sally Horner does not diminish Lolita’s brilliance, or Nabokov’s audacious inventiveness, but it does augment the horror he also captured in the novel.

WRITING ABOUT VLADIMIR NABOKOV daunted me, and still does. Reading his work and researching in his archives was like coming up against an electrified fence designed to keep me away from the truth. Clues would present themselves and then evaporate. Letters and diary entries would hint at larger meanings without supporting evidence. My central quest with respect to Nabokov was to figure out what he knew about Sally Horner and when he knew it. Through a lifetime, and afterlife, of denials and omissions about the sources of his fiction, he made my pursuit as difficult as possible.

Nabokov loathed people scavenging for biographical details that would explain his work. “I hate tampering with the precious lives of great writers and I hate Tom-peeping over the fence of those lives,” he once declared in a lecture about Russian literature to his students at Cornell University, where he taught from 1948 through 1959. “I hate the vulgarity of ‘human interest,’ I hate the rustle of skirts and giggles in the corridors of time—and no biographer will ever catch a glimpse of my private life.”

He made his public distaste for the literal mapping of fiction to real life known as early as 1944, in his idiosyncratic, highly selective, and sharply critical biography of the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol. “It is strange, the morbid inclination we have to derive satisfaction from the fact (generally false and always irrelevant) that a work of art is traceable to a ‘true story,’” Nabokov chided. “Is it because we begin to respect ourselves more when we learn that the writer, just like ourselves, was not clever enough to make up a story himself?”

The Gogol biography was more a window into Nabokov’s own thinking than a treatise on the Russian master. With respect to his own work, Nabokov did not want critics, academics, students, and readers to look for literal meanings or real-life influences. Whatever source material he’d relied on was grist for his own literary mill, to be used as only he saw fit. His insistence on the utter command of his craft served Nabokov well as his reputation and fame grew after the American publication of Lolita in 1958. Scores of interviewers, whether they wrote him letters, interrogated him on television, or visited him at his house, abided by his rules of engagement. They handed over their questions in advance and accepted his answers, written at leisure, cobbling them together to mimic spontaneous conversation.

Nabokov erected roadblocks barring access to his private life for deeper, more complex reasons than to protect his inalienable right to tell stories. He kept family secrets, quotidian and gargantuan, that he did not wish anyone to air in public. And no wonder, when you consider what he lived through: the Russian Revolution, multiple emigrations, the rise of the Nazis, and the fruits of international bestselling success. After he immigrated to the United States in 1940, Nabokov also abandoned Russian, the language of the first half of his literary career, for English. He equated losing his mother tongue to losing a limb, even though, in terms of style and syntax, his English dazzled beyond the imagination of most native speakers.

Always by his side, aiding Nabokov with his lifelong quest to keep nosy people at bay, was his wife, Véra. She took on all of the tasks Nabokov wouldn’t or couldn’t do: assistant, chief letter writer,

first reader, driver, subsidiary rights agent, and many other less-defined roles. She subsumed herself, willingly, for his art, and anyone who poked too deeply at her undying devotion looking for contrary feelings was rewarded with fierce denials, stonewalling, or outright untruths.

Yet this book exists in part because the Nabokovs’ roadblocks eventually crumbled. Other people did gain access to his private life. There were three increasingly tendentious biographies by Andrew Field, whose relationship with his subject began in harmony but curdled into acrimony well before Nabokov died in 1977. A two-part definitive study by Brian Boyd is still the biographical standard, a quarter century after its publication, with which any Nabokov scholar must reckon. And Stacy Schiff’s 1999 portrayal of Véra Nabokov illuminated so much about their partnership and teased out the fragments of Véra’s inner life.

We’ve also learned more about what made Nabokov tick since the Library of Congress lifted its fifty-year restriction upon his papers in 2009, opening the entire collection to the public. The more substantive trove at the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection still has some restrictions, but I was able to immerse myself in Nabokov’s work, his notes, his manuscripts, and also the ephemera—newspaper clippings, letters, photographs, diaries.

A strange thing happened as I looked for clues in his published work and his archives: Nabokov grew less knowable. Such is the paradox of a writer whose work is so filled with metaphor and allusion, so dissected by literary scholars and ordinary readers. Even Boyd claimed, more than a decade and a half after writing his biography of Nabokov, that he still did not fully understand Lolita.

What helped me grapple with the book was to reread it, again and again. Sometimes like a potboiler, in a single gulp, and other times slowing down to cross-check each sentence. No one could get every reference and recursion on the first try; the novel rewards repeated reading. Nabokov himself believed the only novels worth reading are the ones that demand to be read on multiple occasions. Once you grasp it, the contradictions of Lolita’s narrative and plot structure reveal a logic true to itself.

Unspeakable Acts

Unspeakable Acts The Real Lolita

The Real Lolita Women Crime Writers

Women Crime Writers